Global Plus: Breaking barriers, increasing understanding, one joke at a time

We could use a good laugh.

The threat of terrorism, socioeconomic inequality and disillusionment with politics and politicians have contributed to a rise of social and political polarization, populism and extremist ideologies.

With a growing sense of global uncertainty, the need to try to make sense of everyday life is real. You might say frustration and fear have created more opportunities for comic relief.

And for moving past religious stereotypes that divide nations and regions.

Yes, humor can be offensive and divisive, especially jokes about sensitive issues, such as race and religion. One’s sense of humor may be another’s offense. The Muhammad cartoon controversy and the Charlie Hebdo affair are only small illustrations of the fierce conflicts that have erupted over issues of inappropriate or offensive humor and the limits of freedom of expression.

We have seen the downside. But there is a big upside.

As a social and relational form of communication (we tend to laugh together) and a form of encounter, humor has the potential to help us connect with others in different social settings, foster human relations and build bridges across different and diverse communities.

It also offers another way to look at the world and to see things differently. Jokes touch on uncomfortable or sensitive issues, which they bring out in the open, in an attempt to break taboos, stigmas and social barriers, and expose hypocrisy.

Humor is often regarded by scholars as a soft

power. But research is showing that laughter can cut through tension and help bring people together and help promote social cohesion and integration.

Several studies have shown how humor is being used to fight extremism. It also has been used to expose corruption and war crimes, for example in British comedy writer Jane Bussmann’s book about Uganda, The Worst Date Ever: or How it Took a Comedy Writer to Expose Africa’s Secret War.

New technologies that have allowed comics to reach global audiences, a burgeoning generation of Muslim comics reaching out to Western audiences, and even a growing movement of interfaith comedy are all setting the stage for humor to be a force in helping to increase understanding and reduce conflict.

If humor works, then a key question becomes: Will we choose to laugh together?

Life is serious all the time, but living cannot be. You may have all the solemnity you wish in choosing your neckties, but in anything important such as death, sex, and religion, you must have mirth or you will have madness.

G.K. Chesterton, Christian writer and philosopher.

Joyful faiths

Religion and humor are often viewed with suspicion or great caution at best.

This is partly because institutional religion is typically based on moral truths and on certainty of belief in and conformity to a higher authority and order, aiming to reinforce established norms. In contrast, humor thrives on ambiguity and transgression, on challenging, questioning or deviating from social norms and moral rules.

Yet, religion and humor share more in common than meets the eye.

Many of the world’s religions have longstanding humor traditions, albeit in different forms and degrees. The presence of comedy in Jewish and Christian Scripture, as well as an established tradition of a distinctly Jewish approach to humor as a response to modernity, have been widely recognized and studied.

The greatest Jewish tradition is to laugh,

comedian Jerry Seinfeld said. The cornerstone of Jewish survival has always been to find humor in life and in ourselves.

In the Christian tradition, there is often an uneasy relationship between philosophers and theologians and laughter and humor.

Yet there are many notable exceptions. St. Thomas Aquinas considered a lack of mirth as a vice, joy as a noble human act and virtue in playfulness. Augustine envisioned God as the source of all joy.

But there is a much less visible or established tradition of Muslim humor.

On the one hand, there is the question of the permissiveness of laughter in Islam from a theological perspective, even though there are several passages in the Quran and other Islamic texts highlighting the value of laughter and humor to lift spirits.

On the other hand, there are practical manifestations of humor in the Muslim world, expressed in literature, popular culture and the oral tradition.

This tradition is flourishing with a new generation.

Muslim humor

As part of the Generation M of Muslim millennials who are proud of their faith and dynamically engaged and creative, there is a growing production of humor by Muslims

around the world, such as comedy shows and festivals, TV sitcoms, films, videos, blogs and books.

This is very much visible in the world of stand-up comedy. Muslim stand-up comedians, such as Shazia Mirza in the UK and Aasif Mandvi in the U.S., broke into Muslim comedy in the early 2000s.

But recently they have entered the world of mainstream comedy more visibly and dynamically. Muslim comedians have emerged and are gaining momentum. They are catering to a diverse audience of Muslims and non-Muslims alike, using a distinct sense of humor on or about being a Muslim, across different genres, especially stand-up comedy.

In North America, Europe and Australia alone there is an abundance of Muslim stand-up comedians, such as Imran Yusuf, Tez Ilyas, Bilal Zafar and Guz Khan in the UK, Samia Orosemane and Farid Abdelkrim in France, and Hasan Minhaj, Mohammed Amer and Maysoon Zayid in the U.S., including Muslim women comedians, and more particularly hijabi comedians, such as Salma Hindy and Sadia Azmat.

There are also several comedy festivals, such as Muslim Funny Fest, and comedy tours, including The Comedy Show, The Super Muslim Comedy Tour, Allah Made me Funny, and Arabs Are Not Funny, part of the Arts Canteen initiative in the UK. There are also other types of Muslim comics, including bloggers (for example, The Bearded One in the UK) and vloggers.

Comedy has thus become a novel way with which to respond to the negative charisma

that has been imbued on Muslims since 9/11 and to counter Islamophobic stereotypes; it is also part of an effort to help promote community building around shared core values.

Yusuf, a British stand-up comedian, has a passion for language. He carefully uses his words to bring together socio-political satire and introspection in a comical way. His ethos is that we become who we judge and that by demonising others, we ignore owning our own faults.

The fact that Muslim comedians are entering the world of mainstream comedy suggests a very visible and highly accessible sense of humor, thus challenging the perceived incompatibility between Islam and humor, and between Muslims and laughter.

Challenges remain

Both religion and humor can push us to go beyond our own everyday reality, to search for alternative interpretations and meanings. Ethnic and religious humor (humor about ethnic or religious groups and about religion itself) prompts us to think about the world, including religious or ethnic groups, in a different way. Jokes can challenge stereotypes and engrained assumptions, and help us develop a sense of empathy.

Religion and humor also can help us disengage from our own problems, go beyond our own everyday reality and search for alternative interpretations and meanings. They also have power. Everyday lived religion and humor are situational and bring people together; they can strengthen commonality and help build a common sense of humanity.

But ridiculing or mocking humor can easily lead to humiliation and offence. That type of humor can also perpetuate stereotypes and legitimize or provide implicit approval to express prejudice, which can magnify differences, inflame sensitivities, fuel tensions and lead to conflict.

Some scholars have argued that a good sense of humor is infused with empathy and respect. But does respectful humor risk being boring or not funny at all?

What constitutes acceptable

religious humor and what kinds of reactions can it elicit among different people?

This is a key question, but one that is difficult to answer since humor is relative and culturally embedded. What makes people in a particular group or situation laugh may not translate well or be funny in another.

Who makes fun of whom and about what is also a key question? For example, what happens when someone who is not Jewish or Muslim makes a joke about Jews or Muslims? Is there a so-called universal

kind of religious humor that translates well and is funny in a variety of cultures and religious traditions?

For example, can self-deprecating jokes that make us laugh at ourselves and highlight our human faults create a humorous solidarity among different groups, and also be used to pre-empt prejudice?

Using comedy to focus on issues, not people, can strike the right balance, according to Andrea Tuijten, former co-director of MUJU in the UK. MUJU is an initiative featuring carefully curated creative collaborations between Muslims and Jews.

The synergies between religion and humor, especially their potential role in addressing social challenges, including interfaith relations, especially between Christians and Jews, is another key issue.

Related to this point is a more general question on how humor and laughter can bring together Jews, Muslims and Christians and thus work symbiotically to foster understanding and strengthen relations between these three religious traditions and faith communities.

Here, progress is being made.

Although limited in scope, there are some comedy initiatives with a specifically interfaith perspective and objective to strengthen commonality between different religious communities, especially Christians, Jews and Muslims.

In the U.S., the Funatical Comedy Tour in 2011 was an intercultural and interfaith comedy tour aiming to break stereotypes and bridge gaps between Muslims, Jews, Christians (and other faiths), featuring comedians from the Middle East and South Asia. The One Muslim, One Jew, One Stage show in 2013 was a comedy act and tour featuring a rabbi, Bob Alper, and a Muslim community activist, Azhar Usman, who, in a stand-up gig, put their differences aside and drew on their similarities for laughs. More recently, in March 2017, a comedy show in Los Angeles featured Jess Salomon, a Jewish comedian, and Eman El Husseini, a Muslim comedian, both women from New York city.

In the UK, MUJU’s Muslim and Jewish performance artists use comedy as a means of engaging with and exposing the conflicts and complexities within and between Muslim and Jewish communities. MUJU’s comedy engages with wider social and political trends, comically questioning the politics of representation, poking fun at ignorance and exposing double standards.

Such interfaith initiatives are the seeds for growing comedic openings in the future.

Even if interfaith comic initiatives remain limited in visibility, the successful entry of Muslim stand-ups and other types of comedians from diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds in the world of comedy sheds a ray of hope that humor and religion can undo otherness and minimize the opposition between us

and them

.

Bringing together diverse audiences and creating opportunities for laughing together about sensitive issues, including religion, ethnicity and race, can facilitate dialogue between different groups that might otherwise be difficult.

Breaking barriers and building bridges across diverse communities can sometimes happen one joke at a time.

LINA MOLOKOTOS-LIEDERMAN is a researcher in sociology of religion in London, UK, currently working in the area of religion and humor. She received her doctorate from the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris.

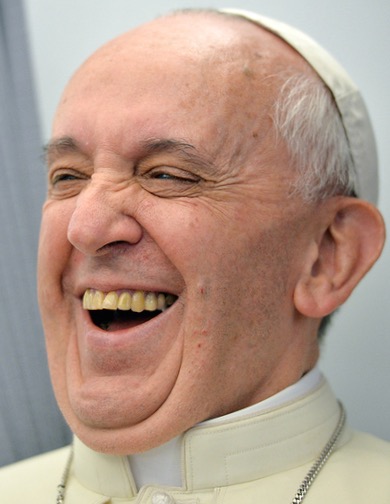

Image by Alex Luyckx, via Flickr [CC BY 2.0]

Image by Diamond Geyser, via Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Resources

- ARDA National Profiles: View religious, demographic, and socio-economic information for all nations with populations of more than 2 million. Special tabs for each country also allow users to measure religious freedom in the selected nation.

- ARDA Compare Nations: Compare detailed measures on religion on any nation, including religious freedom and social attitudes, with similar measures for up to seven other nations.

- Institute for Islamic-Christian-Jewish Studies. The institute’s Humor and Religion Series features several scholars reflecting on issues surrounding the intersection of faith and humor.

- The Bearded One. The blog of Imran Khan uses humor to offer different perspectives on Islam.

- The Joyful Noiseletter. A Christian humor publication featuring leading cartoonists and humorists.

- Holy humor – Muslim & Jewish Comics. Listen to a Jewish and Muslim comic who perform together discuss the power of humor to increase understanding.

- MUJU. This initiative features carefully curated collaborations between Muslims and Jews.

Articles

- Briggs, D. Not Just A Joke: Studies Reveal How Religious Humor Can Break Through Prejudice. Research indicates humor can build social ties and bond diverse people together.

- Michael, J. American Muslims stand up and speak out: trajectories of humor in Muslim American stand-up comedy. The article analyzes how Muslim American comedy intends to influence opinions held not only about Muslims but also amongst Muslims.

- Hirzalla, F., Van Zoonen, L. and Muller, F. How Funny Can Islam Controversies Be? Comedians Defending Their Faiths on YouTube The article analyzes whether humor can release some of the tension in Islam controversies and open up new directions for dialogue.

- Hirzalla, F. and van Zoonen, L.

The Muslims are coming

: The enactment of morality in activist Muslim comedy. Using as a case the documentaryThe Muslims are Coming!

, this article investigates how activist Muslim comedy aims to bring together Muslims and non-Muslims. - Roberts, R. C. Humor and the Virtues. The article explores ethical dimensions of humor.

- Velasquez-Manoff, M. How to Make Fun of Nazis. The article shows how humor is used as a tool to highlight the absurdity of Neo-Nazis and white nationalists in Germany.

Books

- Attardo, S. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Humor Studies. The encyclopedia explores the concept of humor in history and modern society in the United States and internationally.

- Bussmann, J. (2010). The Worst Date Ever or How it Took a Comedy Writer to Expose Africa’s Secret War. The comic memoir exposed corruption and war crimes in Uganda.

- Carroll, N. (2014). Humour: A Very Short Introduction. The book is an introduction to the nature and value of humour and all of the leading theories.

- Geybels H., and Van Herck, W. Humour and Religion. Challenges and Ambiguities. The book highlights the importance and functioning of humour in different world religions. Exploring the major religious cultures, the book looks at more constructive aspects to the relation between humour and religion, with humour seen as a pathway to spiritual wisdom.

- Janmohamed, S. Generation M: Young Muslims Changing the World. This book explores what it’s like to be young and Muslim today and the belief in an identity that combines both faith and modernity.

- Martin, J. Between Heaven and Mirth. The author, a Jesuit priest with a busy media ministry, argues that a healthy spirituality and a healthy sense of humor go hand-in-hand.