IARJ Global Dialogue: Story Ideas for Religion Writers around the World

EDITOR’S NOTE: In 2020, regular readers of the IARJ website will be able to enjoy occasional columns featuring stories that connect religion writers on different continents. The IARJ’s mission is building peer-to-peer relationships that promote fairness, accuracy and balance in reporting on the vital role of religion in our world. Earlier, we featured a joint column about the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Here is our latest IARJ Global Dialogue:

The Journalists: Niraj Warikoo and Larbi Megari

Niraj Warikoo is the religion reporter for the Detroit Free Press. Here’s an online biographical sketch of Niraj. The best way to see Niraj’s ongoing work is to follow his Twitter feed. Larbi Megari is a London-educated Algerian print and television journalist who serves as co-managing director for the IARJ. You can find Larbi’s bio on our IARJ website. Larbi is most active in the Arabic-language portion of this website—or, you can follow him on the IARJ’s Twitter feed.

Story Ideas for Religion Writers around the World

Faith in a Time of Coronavirus

The goal of this dialogue is Story Ideas for Religion Writers around the World.

The first idea comes from Larbi Megari.

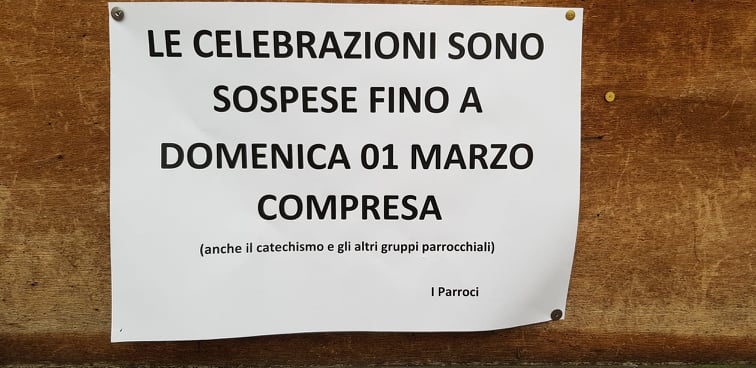

LARBI WRITES—Religion is the world’s biggest social network. As our Italy-based colleague Elisa Di Bendetto just reported for our website: In the age of Coronavirus, that means religion writers have many stories to report these days about how religious customs can be dramatically transformed by COVID-19. Just a week ago, our IARJ board member Peggy Fletcher Stack just reported on these challenges from an American perspective. (Note: Peggy’s articles may not be accessible in some parts of the world.)

In hard-hit Italy, Catholics have been startled by church closings—so have many tourists hoping to see religious landmarks. Meanwhile, in Iran, government orders to suspend Friday prayers also are a dramatic change, since these community prayers have been a defining part of Iranian culture since the era of the Islamic Revolution. The idea is so startling that some religious leaders in Iran have refused to quit gathering on Fridays. This is a tough, ever-changing story to report. The status of religious gatherings—from church closings to Friday prayers—is changing across the world’s many countries on a weekly basis.

Whether reporting on Christian responses in the U.S., or Catholic closings in Italy, or Muslim changes in Iran, journalists have a real challenge reporting on the whole range of religious opinions. We need to avoid any temptation to take sides in reporting on these unprecedented changes. For example, we may be tempted to report mainly on the easily available official announcements, but regional experiences may wind up varying widely if we dig deeper. This is a big story this story this year—and difficult to follow for journalists.

Iran and Shia Muslims in the West

The next idea came from Niraj Warikoo with response from Larbi Megari:

NIRAJ WRITES—Journalists need to look closely at the impact of the United States’ conflict with Iran on Shia communities in the West. How did the January 3, 2020, targeted killing of Iranian major general Qasem Soleimani, and a subsequent Iranian attack, heighten anxieties related to Shia communities in the West? Is this escalation of conflict affecting civil rights? Sparking racism and Islamophobia? Will it lead to more profiling and investigations of citizens and their families? How are Shia families dealing with this increased tension?

LARBI WRITES—I totally agree with Niraj that we, as religion writers, should look for the consequences of international conflicts on religious minorities. We should keep in mind that, while scholars and officials may understand distinctions between Shia and Sunni communities, the general public frequently lumps all minorities together. So, public backlash may target many different groups. For example, over the past two decades, Sikh men with their distinctive turbans have often been mistaken for Muslims in the West and have suffered hate crimes as a result. The potential for grassroots backlashes can happen anywhere in the world. Within the Arab and Muslim world, journalists should look for signs of problematic treatment of minorities, including non-Arabs and non-Muslims who are living in predominantly Arab or Muslim countries.

Minority Communities Helping Homelands

NIRAJ WRITES—The Chaldean (Iraqi Christian) and Yazidi communities had to flee due to years of conflict and the rise of ISIS, and are now trickling back. But they’re facing challenges. Reporters should explore how immigrant communities scattered across Europe, the United States and Australia are helping out with efforts to rebuild their homelands.

LARBI WRITES—Niraj is pointing to part of a much larger story. Members of the Arab, Muslim and other diasporas, now scattered around the world, are contributing in important ways to their families still living in their homelands. Some immigrants are sending their money via banks, but others prefer to send their savings in cash through a range of different networks. Religion writers could look into these ways that families—separated by vast distances—nevertheless continue to help each other. In such stories, journalists also could look into how these financial transfers happen, what these religious groups say about banking in general, and how members of these faiths regard the sharing of money and family resources. In contrast, there also are good stories to report on those who choose to make a complete separation from their homeland communities for various reasons.

As Hate Rises, How Do Communities Defend Themselves?

NIRAJ WRITES—With a well-documented rise in antisemitism in the U.S. and Europe, how are Jewish communities coping? Some are doing interfaith work and reaching out to law enforcement officials. News stories about increased spending on security have appeared in Detroit and New York City. Other metro areas also are investing in new systems. Reporters should look in particular at Orthodox communities, who face more risks because of their unique dress and appearance that makes them more vulnerable to hate attacks. Almost any organized Jewish community across North America and Europe will be increasing security in 2020. Also, law enforcement officials are developing new relationships and protective programs.

LARBI WRITES—These are important stories. Especially for minority groups, there is a constant awareness of the need for security—especially when one’s faith and culture involves distinctive appearance. Of course, reporters have a relatively easy time finding and interviewing men and women who maintain traditional garb or perhaps hair or markings on the skin. The greater challenge is finding members of these minority groups who remain active in their faith but have chosen to avoid religious garb partly due to security concerns. Sharing these stories about the daily anxieties among men, women and children is an important way to help humanize this difficult personal challenge in an era of rising hatred.

Faith and Immigration

NIRAJ WRITES—Then, let’s look deeper this year at the way communities are helping at-risk people to cope in this anxious time. We should look at how religious groups—from churches to Jewish groups to Islamic mosques—are helping out immigrants and refugees amidst increasing xenophobia. In Michigan, two congregations have become sanctuaries for some immigrants. Others are working in various ways to help refugees across the United States. Reporters across Europe and the U.S. could find important stories about religious groups becoming more active in caring for immigrants and refugees.

LARBI WRITES—I agree, because this story idea Niraj is raising could be reported almost anywhere around the world. Religion writers on nearly every continent can find compelling stories about religious groups trying to help immigrants and refugees cope with their circumstances. It is common in many regions to see—for example—a Christian charity taking care of a Muslim refugee, or a Jewish charity taking care of a Christian immigrant coming from Africa looking for a decent life. I have also seen fascinating stories about Sikhs helping Rohingya refugees with food and medication. These can be deeply inspiring multi-faith stories that readers around the world will want to share via their own social media.