IARJ @ Work: Reporting from Jakarta, Endy Bayuni asks, Would a more secular Indonesia be wealthier?

EDITOR’S NOTE: In this IARJ@WORK

series, we publish articles that illustrate the work of our members around the world. Endy Bayuni is the executive director of our organization and gave permission to publish this recent article that appeared in The Jakarta Post.

That Indonesians possess strong religiosity is a well-established fact. A first-time visitor to the country would be amazed at how much Indonesians build their lives around their faith, observing the teachings and practicing the rituals of whatever religion they follow.

But is this religiosity getting in the way of the world’s fourth most populous country becoming more prosperous? Was Karl Marx right in his dictum that religion is the opium of the people

and that most Indonesians put the spiritual ahead of the material world?

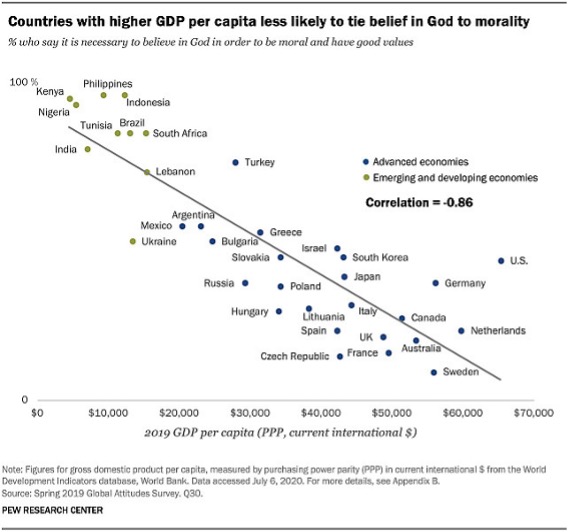

An international survey found a strong inverse correlation between religiosity and the wealth of nations, with the inevitable conclusion that the more religious nations tended to have lower per capita gross domestic product (GDP), while the more secular countries tended to be wealthier.

In a Pew Research Center survey of 34 developed and emerging economies conducted last year, Indonesia topped the list for positive responses to the question, Is it necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values?

A staggering 96 percent of Indonesian respondents replied yes.

This apparently has little to do with Islam, the professed faith of 88 percent of the country’s 270 million population. Indonesia shares the top spot with its neighbor the Philippines, a predominantly Catholic nation. Is this something to do with living in an archipelagic nation or areas prone to natural disasters like volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, tsunamis, typhoons, floods and landslides?

Other countries that ranked high in positive responses to the above question include Kenya with 95 percent, Nigeria with 93 percent, Brazil, South Africa and Tunisia all with 84 percent, and India with 79 percent. The people in these countries also connect belief in God with good moral conduct and values.

At the other end of the extreme are secular countries where a minority of the population link faith and morality. In Sweden, only 9 percent of respondents held this view, followed by the Czech Republic and France with 14 and 15 percent, respectively. The culture wars in the United Sates have slowed secularization, with 44 percent of Americans still believing there was a link between faith and morality. Closer to Indonesia, 19 percent of Australian respondents held this view, followed by 39 percent of Japanese respondents and 45 percent of South Korean respondents.

The pattern that has emerged from the survey suggests a strong negative relationship between religiosity or spirituality on the one hand, and the level of prosperity on the other. The Pew Research Center analyzed the survey results and found a correlation coefficient of minus 0.86, with a value of 1 indicating perfect correlation and 0 indicating no correlation.

The correlation analysis only establishes the relationship between these two variables and does not explain the cause-and-effect relationship. We cannot say that religiosity gets in the way of nations becoming more prosperous any more than we can say that more wealth leads to less religiosity or spirituality. This is for social scientists and religious scholars to answer.

All we can deduce from the survey is that Indonesia is grouped with other countries where religiosity is high and prosperity is lower than more secular countries.

Some may even argue that Indonesia’s economic history in the last two decades show that the two variables are actually complementary.

The economy has been growing more rapidly than ever before, yet at the same time, the spiritual life of the nation has been booming, evidenced in part by the nation becoming more religiously conservative. A time series analysis, rather than a cross-country comparison, may actually suggest a positive correlation between the two variables.

Islamic conservatism may account for the high religiosity shown by the survey results, but we should not forget that communities of minority religions that live in pockets across the archipelago count among the world’s most devout of their chosen faiths.

Visitors to the country will find well-attended churches in North Sumatra, North Sulawesi, Maluku and East Nusa Tenggara, where Christianity and Roman Catholicism dominate.

Many Indian visitors express surprise at the depth of the Hinduism that is practiced on Bali.

Spiritual beliefs, including mysticism, also run high among those who profess to following the major religions. Kejawen, the traditional Javanese belief system, is widely practiced by many who claim to be Muslim or Christian. And there are hundreds of other homegrown faiths that are still practiced in various parts of the archipelago, as opposed to imported religions from the Middle East or India.

Living with the constant threat of natural disasters may partly explain this phenomenon as people turn to God in enduring severe hardships, if not for salvation, then certainly for comfort. This also means that Indonesians tend to have a higher pain threshold than most other nations.

There is no denying that spirituality and religiosity form a large part of the daily lives of most Indonesians. The state reinforces this: The first of the five principles in state ideology Pancasila is belief in one God

, and it is not uncommon for both private and official events, including international ones, to open with prayer.

The high religiosity of the citizenry is something that any government, national or local, must take into account when formulating its policies. When it comes to economic policies, growth is important but equality is even more so as a value highly touted in almost all faiths.

Putting aside the pandemic-induced recession, Indonesia’s economy is doing fine amid the high religiosity of its people and is still on track to becoming the fourth largest in the world by 2045. Would the economy grow more rapidly if Indonesia was just a little bit more secular? God only knows.

Care to learn more?

Here is a link to the original 2020 Pew study, which includes additional information about the team’s findings.

The writer is senior editor of The Jakarta Post and executive director of the International Association of Religion Journalists (IARJ). This article, which first appeared in in The Jakarta Post in September 10, 2021, is republished here with the writer’s permission.