Tips for journalists covering the Jewish New Year 5777

Around the world, the most important Jewish holidays of the year are coming. Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, starts at sundown on October 2 (here’s a column on the holiday by IARJ member Stephanie Fenton) and Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, starts at sundown on October 11 (here’s a column on that holiday by Stephanie). This is an annual challenge for journalists, especially in parts of the world where the Jewish minority is often overlooked in news media. This series of tips is provided by Joe Grimm, who runs the Bias Busters program at the Michigan State University School of Journalism in the U.S. For years, Joe has trained journalists to report on religious, cultural and racial minorities.

Journalists who write about religion know that it takes immense care to write about any faith group. There is nothing simple about it. Student journalists at Michigan State University who published the book 100 Questions and Answers about American Jews learned that lesson early as they tried to just scratch the surface with answers about one of the world’s oldest religions.

The guide is part of a series of cultural-competence guides published by the MSU School of Journalism. This book on Judaism was the second in our series of guides dealing with faith. The first was 100 Questions and Answers About Muslim Americans. More religion guides are planned in the series, which will soon number 12.

The process the students use in their research and writing pointed out some intriguing similarities between journalism and Judaism.

As we write in the book: Questioning and dialogue are deeply ingrained in Jewish tradition, beginning with the study of scriptural texts. Questioning keeps Judaism alive and relevant in changing times. Questions are also central to journalism. We began this guide by asking dozens of Jewish people with different perspectives and practices what they thought people wanted or needed to know about them. Some questions are simple, but the answers seldom are.

Editing the guide felt like a dialogue among learned elders, all striving to find the truth by peering through their own and others’ lenses. One reviewer would question a fact or interpretation and share it with colleagues. Some would suggest that the editor consult other people. In some cases, such as whether to title the guide American Jews

or Jewish Americans,

there were even votes. At no point, however, did the process bog down. All were drawn toward an accurate finished guide.

Through hundreds of questions and the dialogue, we learned not just about Judaism, but how it should be covered.

In the foreword, Rabbi Bob Alper cited an old line, When there are two Jews, there are three opinions.

It is a reflection of this rigorous search for truth.

Tips for Covering Judaism

These are some of the lessons in the guide.

- Jews do not

all think alike

: Avoid stereotypes about Judaism. There are many streams of Judaism and there is a respectful room within each branch for disagreement. As journalists, we can’t talk to one or two people and think we have captured the essence of Judaism. Language such asit depends,

orsome believe

are not just wiggle words. They describe the actual situation. - Religion and cultures overlap: This contributes to Judaism’s diversity. Three of the main cultures within Judaism are: Ashkenazic, with roots in eastern, central and parts of Western Europe; Sephardic with roots in the region of Spain and Portugal, parts of Western Asia, Greece and former Spanish colonies; and Mizrachic with roots in the Middle East or northern Africa. Combinations of religion and culture shape each family’s or each community’s community’s traditions and approaches to culture. These centuries-old roots can be manifest in varying styles of worship, food and cultural traditions. A

Jewish food,

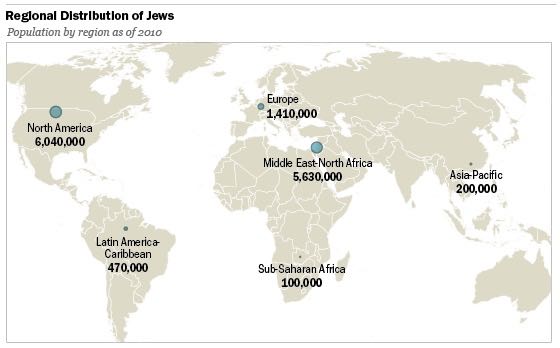

for example, is defined in many ways in many different communities. If you are writing about a particular recipe for the holidays, you might more accurately refer to the food as Middle Eastern or Spanish, rather than universally Jewish. - Judaism is global, but not in huge numbers: There are approximately 13 million to 14 million Jewish people in the world. They make up 0.2 percent of the world’s population and live in scores of countries. More than 80 percent of the world’s Jewish population lives in Israel and the United States—but Jews live in every region of the world.

- The religion is dynamic: Jews as a nation of people date back about 4,000 years to Abraham, his wife, Sarah, and their son Isaac and grandson Jacob. Journalists in Muslim countries are familiar with these founding figures, since Islam branches from Abraham’s son Ishmael. But Muslims and Jews do vary in the way they retell these ancient stories, so take care if you come from a Muslim background and hear references to the biblical era in your reporting on Judaism. As a religion, Judaism dates to about 1400 Before Common Era (BCE). Over that time, Jewish practices have adapted in response to contemporary realities and new denominations have been created in response to contemporary realities.

- It has a shared textual tradition: Judaism was the first formal monotheistic religion. There are connections among basic texts of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. These three monotheistic religions recognize Abraham, Moses and Jesus, but in different ways.

- The Jewish calendar: It uses both the moon phases—as in Islam—but also the time of the solar year. This means that Jewish holidays remain generally in the same seasons of the solar year, down through the centuries. That’s because, unlike Islam where the holidays continue to move each year, the Jewish calendar occasionally adds a “leap month” in the spring to keep holidays in the same season.

- Holidays begin in the evening: The Jewish day begins at sunset and runs until the next sunset. This means that religious holidays start with an evening service and continue through most of the next day.

- Spellings vary: Hebrew and Yiddish (there is no language called

Jewish

) are rooted in culture and borrow from other languages. The dominant language, Hebrew, has 22 consonants and small marks calledvowel points

above, beneath or beside the consonants. When Hebrew words are translated into vowel-dependent English, different spellings result. This is how we get one word spelled many ways in journalism, for example: matzah, matzaa and matzoh. Consult journalism style guides in your part of the world for the most common spellings in your region. Many journalists now tend to default to Wikipedia spellings, so their readers can more easily learn more by easily finding these terms in the online encyclopedia. - There is no central authority: Local congregations and communities are the building blocks of Jewish leadership. They are led by a rabbi, which means teacher. There is no worldwide Jewish leader—no

pope

in the Jewish religion. Many nations, including the United Stated, do not have national Jewish leaders, either. Instead, some have leadership councils. Some nations do identify achief rabbi,

but that does not mean that Jewish families and local communities feel bound by national leaders. - Temple and Synagogue can mean different things: Both are houses of worship, but some streams of Judaism reserve the word

Temple

for the original structure built at Jerusalem and pray for its restoration by God. Some local groups refer to the structure in which they meet as ashul

or acommunity.

Jewish houses of worship are not called churches. Check carefully in your region of the world for the proper words—and spellings—used by the people you are interviewing.

Care to read more?

- FROM THE IARJ—Please follow the IARJ on Twitter and Facebook. If you sign up for our Twitter feed, you’ll see some interesting examples of coverage of the Jewish High Holidays featured in our news items. Also, encourage friends to follow our Twitter feed, which provides fascinating news from around the world in several languages. The IARJ Twitter feed will give you a far more diverse window into the world’s religious and cultural diversity. If you are a journalist covering religion, consider becoming a member of the IARJ.

- FROM THE ASSOCIATION OF RELIGION DATA ARCHIVES (ARDA)—You’ll find very useful information and free online tools to help in reporting on religious minorities. One of the most powerful is ARDA’s Compare Nations set of tools. Enter the name of a nation and you’ll find not only background information on that country, but also an Adherents tab that breaks down religious affiliations. If you add a second or third country, you can easily compare nations. You may find ARDA’s Religion Dictionary useful. And, you’ll also find a very helpful array of maps and charts provided by ARDA.

- FROM THE MSU SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM—The book mentioned in this article, 100 Questions and Answers about American Jews, is available from Amazon. While specifically written for readers in the U.S., the book is packed with information that is relevant to journalists around the world. The university’s Muslim Guide also is available through Amazon.