Eight Tips for Covering Religion Outside Your Home: The Arab Maghreb

Reporting outside your native region carries many challenges. Among these is knowing how to handle yourself appropriately and improve your odds for getting the best story that you can. The IARJ is offering this occasional series on how to work in lands that you may not be familiar with. Larbi Megari, the author of our first report, is the IARJ’s Web Editor and a resident of Algeria.

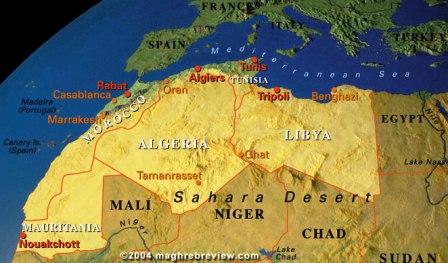

When covering the Arab Maghreb, it’s important to realize that the eastern and western regions of the Arab world as a whole are very different in their experience and application of Islam. In the east, Islam has a longer history and traditions have been handed down for generations. In the west, by way of contract, citizens until recently enjoyed a more European style of life. Only through what Muslim scholars call Sahwa (Islamic Renaissance or Revival, which is a movement of thoughts and behaviours brought to North Africa during the 70s and strengthened after the Iran Islamic Revolution in 1979) did people of the west started trying to live a religion-oriented life.

This east-west distinction carries over to the legal system, as well. In the east, civil laws and legislatures are taken from and based upon Sharia (Islamic law, which consists of the Koran and the Prophet’s Sayings). In the west, however, civil laws and legislatures are not based upon Sharia. The exception to this are family laws governing marriage, divorce, and heritage, which are Sharia-based.

Finally, we see the distinction in language. In the east, all people speak more or less pure Arabic. While in the west, the older generation struggles to speak Algerian Arabic, let alone pure Arabic.

With this background in place, I would like to offer eight tips that will help religion journalists make the best of their time in a Maghreb county when there to cover religion in the region.

Tip One: Entering mosques for non-Muslim people

Sharia (Islamic Law) allows non-Muslims to enter mosques. Even the prophet Mohammed used to receive non-Muslim delegations in his own mosque in Medina.

But when covering religion in the Arab Maghreb, be aware that people there do not appreciate seeing non-Muslim people entering their mosques, regardless the circumstances. Even if you receive a green light to enter, be aware this authorization does not necessarily reflect community consensus. So be prepared in the event you are asked to leave.

Tip Two: Talk to the husband, not to the wife

When meeting a couple on the street, try not to talk to the wife unless her husband turns to look for her opinion or he asks you directly to ask her. In Maghreb countries, especially in Algeria, you should always talk to the husband, not to the wife. Otherwise, you risk facing an angry and jealous husband, which is the last thing any reporter wants.

Tip Three: Christianity mixed with colonialism

Owing to the recent histories of Tunisia, Morocco, Libya and Algeria with French and Italian colonialism, many in the Maghreb confuse Christianity the religion with Western colonialism. Even though churches were not involved in any armed fighting during the conflicts with colonials, (in fact many were giving humanitarian aid to the native population), older people still harbour images of aggressive French troops wearing the Cross-lace around their necks. This confusion between Christianity and colonialism is one reason, I believe, why the new archbishop of Algeria was selected from an Arab nation—Jordan.

Tip Four: Lower your expectations: it’s very hard to meet a native Christian or a Jew who openly proclaims his religion

In the Maghreb region, non-Muslim religions have practically no public life, especially in Algeria where Algerian Christians and Jews have no public standing in Algerian society. Their disappearance from public life occurred in two stages. The first came right after the independence of Algeria on the 5th of July 1962, when Christian and Jewish practice were driven underground. Then, during the 10-year civil war of the 1990s, Christians and Jews virtually disappeared following the killing of nine monks in the region of Tebehrine (east of Algeria).

If you wish to get in touch with these religious minorities, you should go through their official representatives here in Algeria. Keep in mind, however, that talking to Christians here is still taboo. If you are able to talk with a Christian, be prepared for questioning from Algerian authorities.

It is possible to meet them on Sundays in churches such as Notre Dames d’Afrique in the western half of the Algerian capital (not an easy location to get to, but a beautiful one), or Sacré Coeur in the city centre of Algiers (a more secure and reachable location). But here, too, you need to lower your expectations, because most of these worshipers are foreigners who are living in Algiers for work, or they are families and relatives of diplomats working in Algiers.

In Tunisia you can visit the Djerba Synagogue, which is located on the Tunisian island of Djerba.

In Morocco, it is considerably easier to speak with Christians and Jews.

Tip Five: Ten years of armed conflict

This tip is concerned with the Algerian people. The 1990s were a real hell on earth for all populations across the country. The real cause of this conflict was religious, so people are disinclined to speak with media in general, and even less inclined to speak with media concerned with religion.

Tip Six: Very religious people

North African people are deeply religious, but in their own ways. In general terms, they do not have as broad an understanding of Islam and Sharia as people do in the Middle East, but they feel a strong connection to their faith and may be very offended if they believe you are questioning their religious beliefs or practices.

Tip Seven: Maliki tradition vs Salafisme

The majority of peoples across the Arab Maghreb are Maliki Muslims, which is the official Muslim tradition recognized by the government. The Maliki tradition almost certainly gained popularity because most people’s ancestors were Malikites.

Lately, however, things have begun to change. Beginning in the late 1980s, Salafism began winning spaces in mosques across North Africa. Originally, Salafism was defined by its unwillingness to not follow the Maliki tradition, or any other tradition from among the three well-known traditions in the Arab world. Today, Malikites are mostly people over 50. Young people either choose not to be Malakites, or very often are Malikites without knowing what the Maliki tradition is. Note, however, that people who are not Malikites are not necessarily Salafists. Salafists are known by their traditional outfits and by their untouched beards. Most of them are young. They are found around mosques, and most of them are working in trading (small businesses).

Tip Eight: Maliki tradition Vs Ibadi tradition

If your destination is Ghardaia (south of Algeria), you have another religious element to deal with. The Ibadi tradition, which most people in this region follow. The Ibadi tradition is that which is followed in Oman.

Tensions between the Ibadi and Marlikis have been ongoing since the 1980s, and continue unabated today. Violence is part of the tension.

In this region, Maliki people are living in locations such as Tniat-Elmakhzen and Daya Ben Dahwa.

Ibadi people are living in other parts of the region such as Ghardaia center, Bni Yezguen, and Benoura.