Global Plus: My Freedoms Are Your Freedoms! The price of religious freedom denied.

Published Courtesy of ARDA

This is a perilous period for religious freedom throughout the world.

On the record, more than nine in ten countries with populations greater than two million have constitutions modeled in part or whole after the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights stating that [e]veryone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion

and has the freedom to manifest [their] religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

But a growing body of research has found that the chasm between promise and practice is wide, with the promises of freedom routinely denied.

In 2009, Asma Jahangir, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion, concluded that discrimination based on religion or belief preventing individuals from fully enjoying all their human rights still occurs worldwide on a daily basis.

And it seems to be only getting worse.

The most recent Pew Research Center report estimates that 83 percent of the world’s population lives in countries with high or very high levels of religious restriction.

There is no region or world religion or secular government that is exempt from denying religious freedoms. Moreover, a consistent research finding is that religious minorities are the most frequent targets for receiving reduced freedoms, increased discrimination and open persecution in the form of physical assaults or imprisonments.

Reduced freedoms are often justified as a necessity for maintaining the peace, yet research is consistently finding that denying religious freedoms is associated with higher levels of social conflict and violence. The consequences can be found everywhere from the communal violence tacitly condoned by Hindu nationalist government leaders in India to the mass closings of churches and mosques in the officially atheist state of China.

Religious and related freedoms today may be compared to the spiritual principle of loving your neighbor, a universal ideal when your neighbor shares your beliefs. But one that is easily discarded when your neighbor has different ideas.

Yet all the research consistently cries out, My freedoms are your freedoms!

Religious Freedom in 2019: Twists of Faith and Power

Still, the principle is hard to put into practice despite the mounting evidence.

In late August, Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi looked back in the Washington Post at the 2013 military coup in Egypt. The action, abetted by secular opposition groups, overthrew the nation’s first freely elected government and effectively ended the great hopes for political freedom raised by the Arab Spring. An important lesson still to be learned, he wrote, is that intolerant hatred of any belief system, including the various forms of political Islam, can have unintended consequences. In the Egyptian case, he noted, The eradication of the Muslim Brotherhood is nothing less than an abolition of democracy and a guarantee that Arabs will continue living under authoritarian and corrupt regimes.

(Barely more than a month later, Khashoggi was killed by Saudi agents.)

More recently, Russian Orthodox leaders who allowed themselves to be so closely aligned with Vladimir Putin paid a price with the mid-December decision of Ukrainian Orthodox leaders to break with the Moscow Patriarchate and establish their own independent autocephalous church.

So why take the risk?

The answer: The temptations are great.

Although religious freedoms are closely associated with the rise and fall of other civil liberties, religion holds a special relationship with the state and larger culture.

Along with providing religious beliefs, symbols and practices for the local community, religious institutions can also serve as a source of unity and division at the regional and national levels. Indeed, one of the fears for governing bodies is that religious institutions can provide organizational form to underlying political and cultural pressures, and be a source of conflict.

For the state, forming an alliance with the majority faith holds the promise of political stability, visible support from the dominant religion and culture, and provides a mechanism for the state to hold more control over the dominant religion.

For religious institutions, these alliances offer opportunities to procure resources from the state and to restrict the activities of competitors. The most obvious competitors are other religions; but cultural and even state institutions (e.g., secular courts, schools, etc.) can be viewed as competing with the dominant religion.

As a result, the alliances often lead to fewer freedoms for minority religions and many other cultural competitors, including movements advocating for other human rights. Even the dominant religions aligned with the state typically face increased restrictions.

Religious Freedom in 2019: Multiple Threats

Currently, Muslim majority countries offer the most obvious examples of how the tight bond between religion and state can curtail the religious freedoms of others.

In Iran, where the constitution states that laws must be based on Islamic criteria,

the laws prohibit Islamic citizens from changing or renouncing their religious beliefs. Moreover, elected leaders must take an oath to support the official religion and the courts are headed by a Shia Islamic scholar and can issue rulings based on Islamic legal sources.

Even in Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation, concerns for the future of democracy were heightened when a popular Christian governor in Jakarta was accused of blasphemy and jailed in what was widely considered a blatant political effort to unseat him.

But the state’s support of a dominant religion also curtails religious freedoms in non-Muslim countries such as India (Hinduism), Myanmar (Buddhism) and Israel (Jewish).

Separating the activities of religious and state institutions, however, offer no assurances that religious freedoms will be honored. Some secular states, especially communist nations, support an ideology that views religious organizations as potential threats.

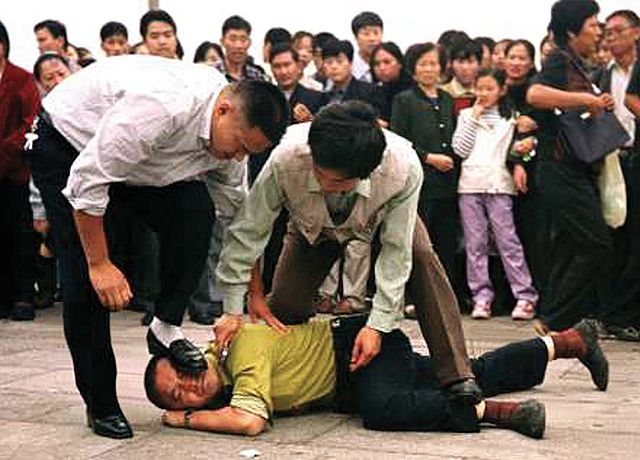

When 10,000 Falun Gong adherents surrounded a Beijing leadership compound in a silent protest on April 25, 1999, the Chinese government’s response was swift and far reaching. By February 2000, the movement was labeled as an evil cult,

an estimated 35,000 practitioners had been detained, 300 jailed, 5,000 sent to labor camps, and 50 committed to mental hospitals.

More recently, the Chinese government’s attempt to Sinicize

all Chinese religions has resulted in Uighur Muslims being sent to re-education camps, with the most credible estimates approaching one million. Protestant Christian churches have also faced sharply increased regulations in 2018. Crosses and sacred images have been removed or destroyed and hundreds of house

churches have been shut down. In several cases entire worship facilities were destroyed and key leaders have been imprisoned or sent to re-education camps.

Other nations are assertive in forcing a public secularism. France, for example, has outlawed the wearing of full-face coverings in public, a law that is clearly targeted at Muslim women. The city of Lorette went further, placing a ban on the wearing of head scarves

and prohibiting the women from wearing full-body swimwear and veils at a public outdoor swimming pool opened in 2017.

It is not just Muslims under attack. A new study of 19 Western-style democracies documented 148 government raids on new religious movements from 1944 to 2018. France alone committed 58 raids.

A more subtle, but far-reaching restriction is the requirement for religious registration.

Over the past 20 years, there have been clear upward trends in the number of countries requesting registration and the practice of using the registration process to discriminate against select groups.

In 2012, Pew researchers found registration requirements discriminated against select religions in 45 percent of the cases.

Consider these examples:

- In Russia, after a flood of new religious groups entered the country following a 1990 law promising religious freedom, new legislation was passed in 1997 requiring a religious group to exist in a community for 15 years before they could qualify for registration. Those unable to meet the registration requirements were denied the rights to own property, publish literature, receive tax benefits, and they faced restrictions on where worship services could be held. When a 1999 amendment to the 1997 law required all groups to re-register or be dissolved, the Ministry of Justice dissolved approximately 980 groups by May 2002.

- Austria requires that groups registered as religious societies must represent a minimum of 0.2 percent of the population (approximately 16,000 individuals) and have existed for 20 years, at least 10 of which were as a confessional society in Austria.

- In Azerbaijan even when the formal registration requirements are seemingly met, local registration offices hold broad discretionary powers in denying registration and the local courts offer few protections from these capricious decisions.

- All of these restrictions have important consequences.

One global study found that a sharp jump occurs in religion-related violence as nations impose greater restrictions. None of the countries with a low

score on government restrictions were reported to have widespread violence related to religion. In contrast, 45 percent of the countries with high

government restrictions had such violence.

But government agencies, policies and legislation are not the only sources for denying freedoms.

Popular culture, the media, academia, religious and political advocacy groups, and biases expressed openly on social media or at the local supermarket can all make a difference.

Everyone has a role in promoting or denying religious freedoms.

Religious Freedom in 2019: Protecting Freedoms

If ever the free institutions of America are destroyed, that event may be attributed to the omnipotence of the majority, which may at some future time urge the minorities to desperation,

French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville observed nearly two centuries ago.

An explosion of global research in recent years both affirms De Tocqueville’s warnings about the tyranny of the majority,

and the various challenges that must be met to protect the right to freedom of belief.

One key to meeting those challenges is preserving an independent judiciary to protect minorities from the legislative will of the majority and the actions of rulers.

But it also means addressing social and cultural pressures to deny freedoms.

Just as social and cultural pressures fuel discrimination by race, ethnicity and sexual orientation, they also fuel discrimination against religious groups.

Dominant religions and dominant cultural groups appeal to the history and culture of their country as motives for denying religious freedoms and even justifying violence. Many national and cultural identities are so closely interwoven with or against selected religions that ensuring religious freedoms for all is perceived as challenging the cultural identity as a whole.

In several countries these pressures have resulted in violence. India’s Ministry of Home Affairs reported that 97 deaths and 2,264 injuries resulted from communal incidents

involving religious communities. The groups most frequently targeted were the minority Muslim and Christian groups.

In the U.S., the FBI reported 1,749 religious hate crimes in 2017 and a national survey of more than 1,300 religious congregations found that nearly 40 percent reported they had experienced a criminal act in the past year. As evidenced by the killing of 11 people at a Jewish synagogue in Pittsburgh and the burning of Muslim mosques, the social pressures go beyond minor acts of discrimination.

The recent data collections all agree, however, that the level of social discrimination against minorities, especially Muslims and Jews, is even higher in Europe than the U.S.

Even without formal restrictions on religion, or government efforts to curb discrimination, cultural pressures, social movements and informal controls can restrict freedoms and promote conflict between groups. Discrimination can remain prevalent in education, employment, and everyday interactions.

And these same cultural and institutional pressures that lead to discrimination against religions, especially minority religions, are associated with increased pressures for more government restrictions.

A 2010 University of Munster study found that more than half of French respondents said practicing the Islamic faith must be severely restricted. Social pressures can also result in local authorities turning a blind eye to discrimination or violence against minority religions.

What often happens then is an ongoing downward cycle of social pressures leading to more government discrimination against religious minorities and the increased government discrimination allowing for more discrimination and violence by non-state actors.

Because freedoms for all are inconvenient, supporting these freedoms are often conveniently overlooked. Turning a blind eye is especially easy when the religious group is a minority. Not only are they less visible, they are often perceived as a threat or are associated with an ethnic or linguistic minority.

Yet, denying religious freedoms pose multiple perils:

- First, supporting religious freedoms serves to defuse potential violence rather than fostering violence.

- Second, denying religious freedoms poses a threat to other freedoms, such as free speech and the freedom to assemble.

- Third, the procedures used to restrict the freedoms of minorities are also used to restrict the freedoms of all religions.

If you oppress people, they will be violent, if you despise the religion of others there will be violence. We have got to recognize other people’s spaces and respect them for who they are,

declared Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu, professor of contemporary African Christianity at Trinity Theological Seminary, Accra

The upshot: When freedoms are uniformly secured for all, the freedoms for even the smallest minority become the freedoms for others.

Simply put: I have more motivation to support your religious freedoms, when your freedoms are my freedoms.

Roger Finke, one of the world’s leading authorities on religious freedom, is Distinguished Professor of Sociology, Religious Studies, and International Affairs at Pennsylvania State University and director of the Association of Religion Data Archives.

David Briggs writes the Ahead of the Trend column on new developments in religion research for the Association of Religion Data Archives.

Image by All India Christian Council, via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Image by Jwslubbock, via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Image by ClearWisdom.net, via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Image by Y. Weeks/VOA, via Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain]

Resources

- ARDA National Profiles: View religious, demographic, and socio-economic information for all nations with populations of more than 2 million. Special tabs for each country also allow users to measure religious freedom in the selected nation.

- ARDA Compare Nations: Compare detailed measures on religion on any nation, including religious freedom and social attitudes, with similar measures for up to seven other nations.

- EUROEL – Sociological and legal data on religions in Europe: For each country, the website presents social and religious data, with information on the principal religions and denominations, religious demography and the legal status of religions.

Articles

- Blumberg, Antonia, Rabbi David Rosen Reveals the Most Dangerous Thing For Religion.

The most dangerous thing for religion is when it’s married to political power,

Rosen argues.When it’s an instrument of political power then it betrays its own message.

- Finke, Roger, and Harris, Jaime. Wars and Rumors of Wars: Explaining Religiously Motivated Violence. The article examines how government and social restrictions on religion have both direct and indirect effects on religiously motivated violence. Not only do these restrictions heighten tensions and increase grievances that potentially feed violence, they increase the social and physical isolation of religious groups.

- Finke, Roger, Presidential Address: Origins and Consequences of Religious Freedoms: A Global Overview The address explores how and why restrictions on religion alter the religious economy and are associated with higher levels of religious persecution, religious violence, and intrastate conflict in general.

Books

- Fox, Jonathan. The unfree exercise of religion: A world survey of discrimination against religious minorities. The book explores religious discrimination against 597 religious minorities in 177 countries between 1990 and 2008.

- Grim, Brian, and Finke, Roger, The Price of Freedom Denied: Religious Persecution and Conflict in the Twenty-First Century. The book provides a compelling argument that religious freedom serves to reduce conflict, while restricting religious freedom is a path to religious persecution and violence.

- Ed. Richardson, James T. Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe. International scholars examine how a number of contemporary societies are regulating religious groups.